Stock Options Revisited

By Joseph Rue, Ara Volkan, Ron Best, and Gerald Lobo

In Brief

An Opportunity to Fix Past Mistakes

The current political and economic environment has reopened the question of accounting for stock options. Unlike in 1995, when FASB last tackled the issue, the public mood favors expensing stock option costs. The major issues left to be decided concern the selection of a valuation model, the revaluation or marking options to market, the frequency of revaluation (i.e., annually versus quarterly), and the period of revaluation and expensing.

The

inability of the capital markets to predict the cash flow consequences of

complex and off–balance sheet financial transactions is one of the main

reasons for the severe decline in investor confidence in financial reports.

A simple, reliable, and understandable valuation model, such as that used

for stock appreciation rights, should be adopted to determine quarterly option

expense until the option is exercised or expires. The opportunity to implement

a sensible solution should be seized while it is still available.

The

inability of the capital markets to predict the cash flow consequences of

complex and off–balance sheet financial transactions is one of the main

reasons for the severe decline in investor confidence in financial reports.

A simple, reliable, and understandable valuation model, such as that used

for stock appreciation rights, should be adopted to determine quarterly option

expense until the option is exercised or expires. The opportunity to implement

a sensible solution should be seized while it is still available.

Stock options have been controversial since Accounting Research Bulletin (ARB)

37 was issued in November 1948. Accounting Principles Board Opinion (APBO)

25, issued in 1972, and FASB Interpretation 28, issued in 1978, continued

allowing sponsors of fixed stock option plans to avoid recording compensation

expense if the exercise price equaled or exceeded the market price at the

grant date.

In 1995, after 12 years of deliberation, FASB issued Financial Accounting Standard 123 (SFAS 123), encouraging, but not requiring, companies to adopt a fair value pricing model to measure and recognize the option value at the grant date and record a portion of this amount as annual expense over the vesting period of the option. Companies that continued using the requirements of APBO 25 had to disclose the pro forma impact of the fair value method on their annual earnings and earnings per share (EPS). SFAS 123, however, did not require the quarterly calculation and disclosure of the option expense. In addition, SFAS 123 did not address the financial impact of options during the period from the vesting date to the exercise date. By allowing the use of competing accounting methods and by not considering the total cash flow impact on sponsoring entities, FASB missed an opportunity to deliver on its stated goal of providing neutral accounting information to assist users in assessing cash flows.

One reason FASB reversed the realization/measurement and financial statement recognition approach advocated in its 1993 exposure draft (ED) and opted for a realization/measurement and footnote disclosure approach in SFAS 123, was pressure from the business community and Congress. It is ironic that the same politicians who forced FASB to stop the expensing of stock options in 1995 are now close to mandating that stock options be expensed because the current political climate demands it.

Another obstacle was the narrow scope of the definitions of liabilities and expenses provided in Statement of Financial Accounting Concepts (SFAC) 6. Under these definitions, promises to issue stock at less than market value are not liabilities, even though such promises have negative cash flow consequences, because the stock could have been sold at a higher price. To its credit, FASB has recognized that SFAC 6 should be revised by issuing a pair of October 27, 2000, exposure drafts (213B and 213C) concerning accounting for financial instruments with characteristics of liabilities, equities, or both, where FASB noted its intention to amend the definition of liabilities and expenses to include obligations that can or must be settled by issuing stock. If FASB makes the changes, the accounting method proposed in this article may be used to measure and report the total cash flow impact of options.

In December 2002, in response to requests by companies that are switching from APBO 25 methods to the preferred method under SFAS 123, FASB issued SFAS 148 to amend the transition provisions and footnote disclosure rules of SFAS 123. The amendments to footnote disclosures extend the SFAS 123 requirements to interim periods. Also, on November 7, 2002, the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) issued an exposure draft of a proposed International Financial Reporting Standard (IFRS) on stock-based compensation that would require the use of a fair value–based method of accounting to measure and expense all such transactions. To harmonize with international standards, FASB issued an invitation to comment (ITC) on November 18, 2002, readdressing whether to require all companies to record and expense the fair value of stock options granted. Revaluing option values at each reporting date and extending the expensing period from the vesting date to the exercise date are, however, issues that remain to be addressed by both FASB and the IASB.

Limitations of Current Accounting

Applying SFAS 123 can result in different treatments for compensation packages that have similar economic (tax, financial, and cash flow) consequences to both the firm and the employee. An article by Don Delves (Strategic Finance; December 2002) reporting on the discussions and conclusions of a panel of experts—including FASB chair Robert Herz, IASB member Jim Leisenring, and Myron Scholes, co-creator of the Black-Scholes option pricing model—at a conference addressing stock option problems, illustrated the issues involved. Number one on the list of top 10 questions that directors of sponsoring companies should ask about stock options was: “What is the true total cost of our stock option package?” The following quotes, taken from Delves’ article, describes the challenge:

The stock option expense is just the [tip] of the iceberg. This is particularly true for corporate boards who are responsible not only for the long-term success of the company but also for representing and safeguarding the interests of the shareholders. This is important because the expense being proposed by the accounting profession doesn’t fully capture the ultimate economic cost of stock options to shareholders. The true economic cost of an option is the spread between the exercise price and market price on the date the option is exercised. ... For example, if an option is granted with an exercise price of $10 when the market price is also $10, the likely “new accounting” expense will be somewhere between $3 and $5. But if the option is exercised five years later when the market price of the stock is $100, then the true total cost of the option is $90. … Someone has to be responsible for this $90 cost and for making sure that the company and the shareholders are getting a return on this investment. If the company is only taking a $5 expense, then the board must make sure that the rest of the cost is tracked and accounted for and that the executives who received this benefit are returning at least that much to the shareholders in improved performance.

FASB should require that the fair value–based measurement and recognition of stock option obligations and expenses continue after the service period ends and until the options either are exercised or expire. A final standard on stock option accounting must ensure that the total amount of wealth that has been transferred from stockholders to executives, and that could be transferred in the future, is reported through the financial statements. Shareholders and other investors must have the same stock option information that is available to company boards and executives.

Current Requirements

For the 200 largest companies, 58% of executive compensation for 1999–2001 was in the form of options. Standard and Poor’s (S&P) announced that it will deduct option expenses from its estimate of core earnings. The popular alternative currently allowed under SFAS 123 would generally not record an expense. Even under the less popular SFAS 123 alternative, which expenses the fair value of options over the vesting period, the result would be based on fair values at the grant date, without incorporating the most current market conditions.

In comparison, for stock appreciation rights (SAR) that entitle employees to receive cash, stock, or a combination based on the appreciation of the market price above a base price, total compensation expense is measured at the exercise date. Therefore, between the grant date and the exercise date, compensation expense is based on the market price of the stock. Although the economic and cash flow consequences of accounting for fixed stock options and SARs appear to be identical (i.e., unfavorable, tax deductible, impact on cash flows either in the form of payments to the holder or issuance of stock at a price lower than the market price), the income statement and balance sheet effects differ substantially.

Measuring Option Value

In January 1986, FASB agreed that the cost of options should be measured at the grant date by using a minimum value (MV) model. FASB changed its mind six months later, stating that costs should be measured using a fair value (FV) model. FASB initially embraced the MV model because it was conceptually sound, objectively determinable, and easily computed. The MV of an option is defined as the market price of the stock minus the present values of the exercise price and expected dividends, with a minimum value of zero. This model, however, uses assumptions and limitations that restrict its applicability for valuing options, such as the assumptions that the stock option is held to maturity (i.e., European call option) and is transferable. More important, the MV model fails to consider the volatility of the price of the underlying stock. The FV models, including the Black-Scholes model, are complex and suffer many of the same deficiencies attributable to the MV models, except that they incorporate the price volatility of the underlying stock when determining the option’s value.

The 1995 ED required the fair value of options to be computed as of the grant date. This amount would then be amortized over the vesting period. The ED argued that options represented probable future benefits because employees have agreed to render future services to earn their options. In addition, the ED asserted that changes in stock prices after the grant date should not impact option measurements, in order to eliminate the volatility that results from the use of later measurement dates. Because FV models like the Black-Scholes model incorporate past market prices in determining option values, it appears that FASB prefers the use of past stock prices in measuring option expense, but not current or future stock prices.

Due to opposition from most of its constituents, FASB backed down from mandating option expense recognition, in spite of some indications that opposition was political rather than financial. Critics argued that recognition of option expenses would increase unemployment by having a negative impact on small companies. There were warnings of plan terminations, loss of key employees by emerging companies, and an inability to raise capital. Exhibit 1 summarizes the characteristics of the pronouncements.

The defenders of the ED argued that they had heard these arguments before. Indeed, the sky did not fall when leases were capitalized in 1976 and pension liabilities were recognized in 1986. They argued that while U.S. capital markets have high informational efficiency, disclosure is not a substitute for recognition. Some argued for treating all options like SARs, going beyond the approach proposed in the ED and the definition of assets/liabilities currently accepted. Lost in the din of the arguments was the fact that the information most valued by stockholders is information that best approximates the cash flow consequences of managerial decisions. Except for the SAR rules in APBO 25, none of the pronouncements in Exhibit 1 accrue the cash flow consequences of stock options over the period from the date of grant to the date of exercise.

SFAS 123 Flaws and Support for Change

The application of Black-Scholes or other fair value models in accounting for stock options results in a static measure. There are no provisions for changing the compensation expense estimate, regardless of changes in the stock price. The major flaw in this approach is that option-pricing models designed to incorporate the latest stock prices for freely traded options will not accurately measure and reflect the economic reality. For example, Lucent Technologies would have reported an option expense of $1 billion in the 2001 financial statements, when these options were practically worthless.

An alternative approach would recalculate option values until the exercise date and thus capture market price movements. Changes in the value of the option would cause changes to be recognized in the periodic option expenses, treating such changes as changes in accounting estimates. It can be argued that revaluation should stop at the vesting date and not be extended to the date of exercise; the employees have become stockholders with an option of holding or selling the stock, just like any other financial instrument. This argument, however, disregards the fact that the expense measures must reflect the economic reality over the life of the option, that is, the ultimate cash flow impact of the options.

While FASB continues to assert that option-pricing models provide reliable and relevant information, the failure to update and revise costs quarterly and annually does not appear to be logical, because it does not incorporate relevant current information about volatility. Furthermore, FASB’s approach is not consistent with accounting for other estimated expenses, where the most recent data must be used for measurement, and amounts must be recognized in interim financial statements. Finally, because of the recent fallout from the corporate accounting scandals, many who opposed expensing options now support it.

Alternative Approaches to SFAS 123

Alternatives based on annual valuations. One alternative approach is to estimate total compensation cost at the end of each year and use the most recent estimate to revise the amount of compensation expense to be recognized in each year of the option period. Under this approach, complex models, such as Black-Scholes and the MV model, are used each year to redetermine the option value. The expense schedule is then adjusted based on this updated valuation. Another approach is to employ a simple model, as opposed to complex models, which would estimate the total compensation cost as the year-end stock price less the exercise price times the number of options. The annual expense is then determined by deducting the expenses already accrued to date from this total expense. In subsequent years, amounts are recomputed based on current closing prices. Changes in option values are treated as changes in accounting estimates. This approach is the same method currently used in accounting for SARs.

While the same total amount of compensation expense may be recognized over the option period, the expense recognized in any given year may differ across the approaches. For the Black-Scholes model, compensation expense recognized declines dramatically over the option period. Under the MV model, however, 95% of the total cost is recognized in the last year. Compensation expense recognized under the simple model is primarily dependent on the change in the stock price from one year to the next.

A recent study compared the income effect of the MV, Black-Scholes, and simple models on a sample of 116 firms (The Journal of Applied Business Research; Lobo and Rue, 2000). The mean annual option expense was $34 million for the Black-Scholes model and $4 million for the MV model. The simple model, however, showed that the actual option expense was $24.5 million. The results suggest that there is a wide variation in measuring expenses, and that all methods can diverge from economic reality (i.e., the impact of options on cash flow).

To provide an indication of the significance of the estimated compensation expense using these models, the study examined the percentage change in annual earnings before taxes that would have resulted from subtracting the alternative measures of compensation expense. The mean percentage decrease was 12.5% for the Black-Scholes model, 1.4% percent for the MV model, and 8.5% for the simple model. In comparison, Botosan and Plumlee (Accounting Horizons; 2001) examined the impact of SFAS 123 on 100 firms identified by Fortune as America’s fastest-growing firms. The three-year average decline in the reported EPS amounts was 40%. These results indicate that there is considerable merit in recognizing compensation expense related to the granting of employee stock options; however, the appropriate approaches for measuring the expense and determining the measurement period are yet to be decided.

Alternatives based on quarterly valuations. Another study explored the annual and quarterly impact of SFAS 123 on 40 firms (The International Business and Economics Research Journal; Best, Rue, and Volkan, 2002). The study measured the impact of option expenses on quarterly EPS using both the static measurement approach required by FASB and a dynamic, market valuation approach. The dynamic approach measured the option expense based on the most recent market information, and allowed the expense to be adjusted upward or downward each period. Forty of the S&P 100 companies that had calendar years and options outstanding as of December 31, 1999, were analyzed; all used the APBO 25 rules. Using the Black-Scholes model and the average exercise period of options disclosed in the footnotes, the values of the options and amounts of option expenses were computed under both the SFAS 123 approach (static expense) and the proposed approach (quarterly recalculation approach). These computations were carried out as of December 31, 1999, and for each quarter in 2000. The effects of including either of these two expenses in earnings were computed in order to observe the significance of the decreases in the APBO 25-based EPS amounts and the differences between the two methods.

Mean quarterly EPS amounts computed under both the static (SFAS 123) approach and the proposed quarterly recalculation approach were 16% lower than the quarterly amounts reported under APBO 25. While the declines from the reported EPS amounts were material (more than 3%), none of the differences between those EPS amounts that would have been reported under SFAS 123 and those that would have been reported under the dynamic approach were statistically significant.

This outcome suggested that for a portfolio containing a large number of companies that operated in a diverse set of industries, both the SFAS 123 and the proposed dynamic option valuation approaches would result in similar EPS computations. Because the SFAS 123 approach involved less effort, it would be preferred in computing an EPS amount for a diversified portfolio. This result, however, must be placed in perspective. Most individual investors and investment advisors mainly focus on the EPS trends of a given company or a given sector, which would be more sensitive to the use of a dynamic option expense measurement method.

To observe the impact of the two option expense measurement methods on the EPS values of companies with similar quarterly financial outcomes, the study separated the sample into two groups. Except for companies with negative returns in the first quarter, all differences between EPS values calculated under the two methods were statistically significant at either 95% or 99% confidence levels. In addition, EPS values based on dynamic (recalculated) expenses were higher than those based on the static (SFAS 123) expenses for firms with negative returns, with the Black-Scholes model assigning lower option values to firms with declining stock prices. As expected, results opposite to those were obtained for firms with increasing stock prices (positive returns). Thus, the dynamic approach to option expense measurement was superior to the SFAS 123 approach in reflecting the cash flow consequences of options (a measure of economic reality) for individual companies. The results of these three studies are summarized in Exhibit 2.

Recommendations

SFAS 123 requirements are inconsistent with accepted approaches to measuring estimated expenses prospectively. The expense measure should reflect the periodic determination of the sacrifice, which is the cash given up by granting stock options. Instead, SFAS 123 adheres to a theory that is appropriate for measuring fixed assets, not financial instruments such as stock options.

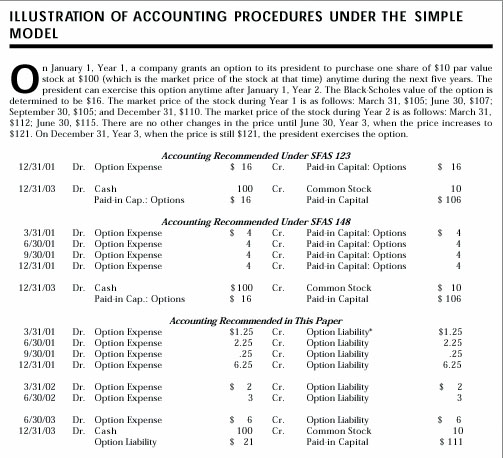

The recently released SFAS 148 mandates the interim disclosure of the measurements required under SFAS 123. FASB may be preparing to eliminate the APBO 25 approach to stock options altogether. In the post-Enron climate, with the IASB and two Congressional committees intending to mandate expensing stock options, FASB must act with deliberate speed. The total option expense should reflect the cash flow impact of granting an option, which is equal to the difference between the market price of the stock at successive reporting dates (or at the final exercise date) and the option price. Research suggests that a measurement-date model (the simple model) provides such a measure and is consistent with the accounting used for SARs (the recommended procedures are described in the Sidebar).

First, the simple model costs little to implement and is easy to use and understand. Although this approach is subject to market price movements, it reduces the volatility inherent in more complex measurements. Information produced by the simple model reflects market conditions at reporting dates, consistent with the results of the studies presented above that show the superiority of market-based, dynamic measures over SFAS 123 measures in providing reliable information. Finally, the simple model provides financial statement users with a forecast of the measure of the cash given up by issuing stock options.

Given FASB’s stated aim of revising the definition of liabilities to include the impact of obligations to issue stock, the recognition of stock options as liabilities may soon become a reality.

©2006 The CPA Journal. Legal Notices

Visit the new cpajournal.com.