Internal Audit Outsourcing

By George R. Aldhizer III, James D. Cashell, and Dale R. Martin

In Brief

Cosourcing as the Solution

Many types of consulting and assurance services provided by external auditors may negatively affect the appearance of auditor independence. Providing internal audit outsourcing services, however, may negatively impact independence in both fact and appearance. As of 2001, because the Big Five controlled at least 20% of the Fortune 500’s internal audit functions, it was only a matter of time before a significant financial reporting fraud involving such conflicts surfaced. Wearing “both hats,” such as Andersen did at one time for Enron, put a firm at risk of being held to a higher standard of fraud detection and, thus, increased liability.

To

minimize an accounting firm’s legal exposure and increase a corporation’s

ability to detect and report fraudulent financial reporting on a timely basis,

the AICPA and SEC should amend their independence rules to eliminate internal

audit outsourcing for all publicly held companies. Instead, full-time, in-house

internal audit departments should be maintained, with cosourcing services

provided by accounting firms to help ensure a world-class internal audit function.

To

minimize an accounting firm’s legal exposure and increase a corporation’s

ability to detect and report fraudulent financial reporting on a timely basis,

the AICPA and SEC should amend their independence rules to eliminate internal

audit outsourcing for all publicly held companies. Instead, full-time, in-house

internal audit departments should be maintained, with cosourcing services

provided by accounting firms to help ensure a world-class internal audit function.

During the last decade, accounting firms’ consulting and assurance practices

have grown in excess of 20% per year. Despite the recent sales and spin-offs

by large firms of their consulting divisions, one of the fastest-growing assurance

services for accounting firms has been internal audit outsourcing. In 1994,

the Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA) estimated that an accounting firm’s

revenues from internal audit services can be up to 10 times that of annual

financial statement audits. In most of these arrangements, the same accounting

firm provides both internal audit and external audit services.

Outsourcing became popular because it appeared to offer significant advantages

to both corporations and accounting firms. A company would benefit by reducing

internal audit costs and by obtaining access to the outsourcing firm’s

broad range of expertise that would otherwise be too expensive to maintain

internally. Costs would be reduced by eliminating overlapping positions and

audit effort, and by replacing fixed-cost with variable-cost employees. The

expected benefits to accounting firms were significant outsourcing fees and

the ability to better balance workloads, because much of the outsourcing work

could be performed during the off-peak summer season. Additionally, it was

expected that the knowledge obtained while performing internal audit activities

would increase the efficiency and effectiveness of the annual financial statement

audit. For example, the understanding of internal controls obtained while

performing internal audit services would enable the auditors to reduce the

amount of work needed to document and test internal controls during the financial

statement audit, as well as enhance the

auditor’s awareness of client-specific fraud risks.

Unfortunately, the purported benefits of outsourcing may have been overestimated. Companies have not been able to reduce their internal audit costs as much as expected, which correlates with a 1991 study that found that companies would not realize cost savings unless accounting firms drastically lowered their hourly billing rates or reduced the scope of audit programs.

More recently, high-profile reporting frauds such as the Enron debacle suggest that outsourcing may not be as effective as a separate external auditor and an in-house internal audit department at detecting and reporting fraudulent activity. As a result of Enron, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 now supercedes the voluntary self-regulation of SEC auditors with the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB). The implementation of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act will also forbid some and limit many nonaudit services that a CPA firm can provide to an SEC client.

While complete internal audit outsourcing is a concern, the same is not true of cosourcing. Cosourcing relies on a strong in-house internal audit department and usually uses external service providers only for nonroutine services where special capabilities are needed.

Compromising Independence in Fact and Appearance

To maintain public confidence in the financial statement audit process, auditors must remain independent. Widespread concern that internal audit outsourcing may compromise independence in both fact and appearance arises mainly because of the magnitude and continuous nature of these services and the lack of strict and enforceable AICPA and SEC independence rules.

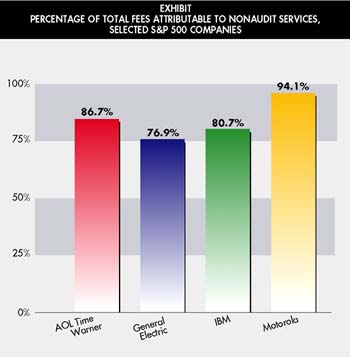

Magnitude and continuous nature of nonaudit service fees. Beginning in 2000, the SEC began requiring all publicly held companies to separately disclose the dollar amount of their external audit fees, their information technology (IT) consulting fees, and all other fees (including internal audit outsourcing fees) paid to their audit firms. In reviewing the 2001 disclosures of nonaudit fees by 307 companies in the S&P 500, the Wall Street Journal found that every one of the companies had purchased nonaudit services from their audit firms during the previous year (based on the SEC’s definition of what constitutes audit services), and, on average, nonaudit fees were nearly three times as large as audit fees. The companies listed included AOL Time Warner (86.7% of total fees attributable to nonaudit services), General Electric (76.9%), IBM (80.7%), and Motorola (94.1%).

While many types of consulting and assurance services may not represent significant fees, the IIA estimated that internal audit services could be 10 times as large as the annual external audit fee. (Purchases of expensive computer hardware or software systems for clients appear to be one of the few types of consulting services where fees may be as large as internal audit outsourcing fees.) Additionally, unlike other consulting and assurance services, internal audit outsourcing is not a one-time service, but rather is offered on a continual basis, thereby increasing the likelihood of closer relationships with client employees. For example, as reported in the Wall Street Journal, Enron outsourced its internal audit department to Andersen in 1993. The accounting firm then hired 40 members of Enron’s internal audit staff. The firm also hired Enron’s internal audit director at a significantly higher salary to continue to oversee the internal audit function. (Andersen later discontinued internal audit outsourcing services, after Enron decided to reestablish a full-time, in-house internal audit department.) At minimum, the magnitude of these revenues and the ongoing nature of the service are likely to have a negative impact on the appearance of independence and may even bias the auditor in favor of the client. According to former SEC Chairman Arthur Levitt, the most flagrant conflict of interest in the Enron case was outsourcing the internal audit function, because Andersen was in effect auditing its own work.

A 2002 Wall Street Journal article reported that, in order to ensure auditor independence, labor unions and shareholders from at least 30 Fortune 500 companies were proposing an initiative that would prohibit external auditors from concurrently providing any type of consulting or assurance service. Shareholders may not realize that a large portion of these consulting and assurance fees may be related to internal audit outsourcing. If internal audit outsourcing were eliminated, the remaining consulting and assurance fees might not appear so large and might not cause the same independence concerns.

Current AICPA guidance. One key reason internal audit outsourcing has continued throughout the 1990s has been the lack of strict and enforceable AICPA and SEC independence rules. On February 1, 2002, the AICPA issued an e-mail to its members stating that its board of directors had approved a resolution to prohibit auditors of public companies from concurrently providing financial systems design and implementation services and from providing internal audit outsourcing services. The e-mail stated that the board did not believe this ban would improve the quality of audits. The ban did not apply to privately held companies.

Prior to this resolution, the primary AICPA guidance was published by the AICPA Professional Ethics Committee as an interpretation under rule 101 that addressed clients’ and CPAs’ responsibilities related to the performance of assurance (or extended audit) services. The interpretation was applicable to situations in which a CPA performed assurance services for an audit client. Its definition of assurance services included assisting in the performance of internal audit activities or extensions of audit procedures beyond those required by generally accepted auditing standards (GAAS).

The interpretation required audit clients to be responsible for establishing and maintaining internal control and for directing the internal audit function. The interpretation specifically required that the client, not the auditor, should assume responsibility for the following tasks:

Unfortunately, many of the Fortune 500 companies that have outsourced internal audit departments to their external auditors have, in large part, not fulfilled these responsibilities. Instead, they have allowed their external auditors to assume these duties with little of the oversight required by the AICPA.

The interpretation also stated that an auditor’s independence would not be impaired by performing procedures considered extensions of the audit scope related to the financial statement audit (e.g., performing analytical review procedures, confirming accounts receivable) even if these procedures exceeded the requirements of GAAS; however, this contradicts guidance issued by the SEC in February 2001 and effective August 2002 (discussed below).

The interpretation went on to state that auditor independence would be impaired if a CPA acts, or appears to act, as a member of management or as an employee of the client. One example cited in the interpretation was referring to the accounting firm as the supervisor or in charge of the client’s internal audit function.

In 2001, the authors made approximately 60 telephone calls to Fortune 500 companies requesting to speak to their internal audit directors. In more than 20% of the cases they were transferred to a voice message from a Big Five firm, which would suggest that, instead of designating a competent individual from within the company to be responsible for the internal audit function, the accounting firms may have actually assumed the role of supervising their clients’ internal audit functions.

Current SEC guidance. In early 2000, the SEC, in response to the demand for further guidance, initially proposed completely prohibiting accounting firms from providing IT and internal audit outsourcing services. By February 2001, however, the SEC had softened its stance and issued only minor amendments to Rule 2-01 of Regulation S-X. While placing no additional limitations on IT consulting services, the amendments limited internal audit outsourcing to no more than 40% of the client’s internal audit work related to internal accounting controls and financial systems unless the client had $200 million or less in assets. Prior to the Enron debacle, this new amendment appeared to have little effect on the extent of internal audit outsourcing provided by external auditors. (It should be noted, however, that this amendment was not supposed to take effect until August 2002.)

The Sarbanes-Oxley Act’s clear prohibition of all internal audit outsourcing related to internal accouning controls and financial systems, for all publicly held companies, addresses this problem. Cosourcing, however, could still be permitted in all other internal audit service areas. These changes should enhance a company’s ability to detect and report fraud by encouraging companies to maintain a full-time, in-house internal audit department and could reduce an accounting firm’s exposure to increased legal liability for failure to detect fraud. The Sarbanes-Oxley Act, however, does not preclude a publicly held company from outsourcing its entire internal audit department to an accounting firm that is not its external auditor.

Litigation Concern: Failure to Detect Material Fraud

Both external and internal auditing standards require only reasonable, not absolute, assurance of detecting corporate fraud by remaining alert to conditions where fraud is most likely to occur. Realistically, however, external auditors may not be as effective at detecting fraud as full-time, in-house internal auditors.

As far back as 1987, the Treadway Commission encouraged corporations to expand their existing full-time, in-house internal audit departments or begin the formation of an internal audit department if none existed in order to increase the likelihood of detecting and reporting material frauds on a timely basis. Recent fraud studies support the Treadway Commission’s recommendations. For example, in 1998, KPMG surveyed top executives within 5,000 of the largest U.S. publicly held companies, not-for-profit groups, and local governments. Respondents consistently rated internal auditors among the entities most likely to detect fraud within their organizations, while external auditors were among the least likely. According to the survey, key factors in detecting fraud included customer and employee notification and anonymous letters. These factors might not be effective if someone such as a full-time internal auditor were not immediately available to receive such communications. This point is especially critical if a firm plans to perform internal audit services only on a part-time basis, such as only during the summer months.

Unlike any other type of assurance service, internal audit outsourcing has been a ticking time bomb. It was only a matter of time before an external auditor that also provided internal audit outsourcing services was entangled with a potentially significant reporting fraud. By wearing “both hats” at Enron for almost five years, Andersen could be held to a higher standard of fraud detection and, thus, subject to significantly higher damages than otherwise. (The June 2002 guilty verdict in the government’s obstruction of justice case against Andersen means that the firm will probably be unable to pay significant damage awards to Enron investors.) This case, however, is not very clear, because Andersen stopped providing internal audit services for Enron in the late 1990s, and it may never be known exactly how much internal audit outsourcing contributed to Enron’s collapse. Conceivably, however, Andersen’s internal auditors may have been more accepting of the special purpose entities (SPE) and their inadequate disclosures if they knew that the SPEs and their disclosures had been approved by Andersen’s external auditors.

Potential Solutions

Possible solutions to enhance the public’s confidence in auditors and to reduce their exposure to litigation include increasing internal audit fraud training budgets and promoting internal audit cosourcing services.

Increase spending on internal audit fraud training. Recent fraud studies indicate that internal audit departments spend a very small portion of their budgets on fraud prevention and detection training. This may be due, in part, to corporate managers who do not fully appreciate the value-added benefits of internal audit fraud training. To help prevent and detect fraudulent financial reporting, corporate managers should significantly increase their internal audit fraud training budgets.

The Enron crisis should have alerted shareholders and managers to the value-added benefits of internal audit fraud training. This training should more than pay for itself by helping to ensure the long-term viability of the company.

Promote cosourcing services. Unlike outsourcing, cosourcing relies on a strong in-house internal audit department as the primary resource and usually uses external service providers for nonroutine services when special capabilities are needed (e.g., special need IT audits, environmental audits, derivative reviews, contract audits, and enterprise-wide risk management services). This allocation of audit tasks creates a synergy that incorporates the strengths of an in-house audit function with the benefits of access to the broad spectrum of capabilities available from an external accounting firm. Cosourcing allows an internal audit department to pursue value-added services that it could not provide because of a lack of time or capabilities. Furthermore, cosourcing should appeal to large firms because, like outsourcing, it generates an attractive new revenue base. Finally, cosourcing could save the company money because routine audit work may be less costly if provided by internal auditors (e.g., extensions of year-end financial statement auditing procedures).

The above approaches would not apply to relatively small privately held companies that normally cannot justify the cost of at least one full-time in-house internal auditor. These companies might be able to justify having an accounting firm provide internal audit services on a part-time basis.

©2006 The CPA Journal. Legal Notices

Visit the new cpajournal.com.