The CEO/CFO Certification Requirement

By Ronald E. Marden, Randal K. Edwards, and William D. Stout

In Brief

Attempting to Deter Management Fraud

The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, section 302, “Corporate Responsibility for Financial Reports,” requires the CEO and CFO of publicly traded companies to certify the appropriateness of their financial statements and disclosures and to certify that they fairly present, in all material respects, the operations and financial condition of the company. But CEOs and CFOs already provide assurances to the auditor in the auditor’s Management Representation Letter, and frequently attach a Management’s Responsibility for Financial Reporting Letter in the corporation’s annual report.

This article discusses the assurances that executive management already provides, compares them with the new Sarbanes-Oxley Act certification, and considers the added value of this latest requirement. It also addresses whether this certification statement will be the final and necessary measure to assure the public that corporate management will take full responsibility, and be held legally accountable, for its actions.

The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 requires the CEO and CFO of publicly traded

companies to issue a statement certifying that the accompanying financial

statements and disclosures fairly present, in all material respects, the operations

and financial condition of the company. A complete listing of companies that

have submitted these statements can be found at www.sec.gov.

Exhibit

1 presents an example of Lowe’s Companies CEO Robert L. Tillman’s

certification statement.

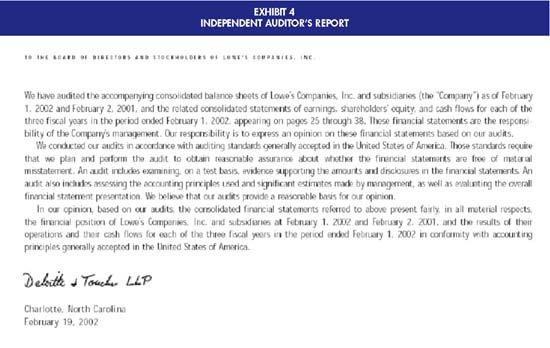

This is not the first time that executive management has been asked to provide some form of assurance on the overall financial statements or the details and assertions that underlie the statements. CEOs and CFOs already provide various statements of assurance to the auditor in the auditor’s Management Representation Letter (Exhibit 2), and frequently attach a Management’s Responsibility for Financial Reporting Letter (Exhibit 3) in their corporation’s annual report just before or after the auditor’s opinion. It remains to be seen whether this certification statement, signed, notarized, and available for public view, will be the final and necessary measure to ensure the public that management will now take full responsibility, and be held legally accountable, for its actions.

Management Assurance

Auditor’s Management Representation Letter. During an audit, management makes many representations to the auditor, both oral and written, in response to specific inquiries or through the financial statements. These representations are part of the evidential matter that independent auditors are required to collect to support the auditor’s overall opinion. Because some representations are obtained only through inquiry, an auditor usually asks the CEO and CFO for a written letter to confirm representations explicitly or implicitly given to the auditor, under the guidance in SAS 85, Management Representations. This written representation letter is to be addressed to the auditor and signed by those members of management with overall responsibility for and knowledge about, directly or indirectly, the matters covered by the representations. Such members of management normally include the CEO and CFO, and others with equivalent positions in the entity.

According to Kiersten Archer and Andrew Leibowitz, in “Management Representation Letters” (Insights: The Corporate & Securities Law Advisor, March 1999), representation letters are important to auditors for several reasons:

Management’s inability or unwillingness to provide representations constitutes a scope limitation of the audit and requires a modified audit opinion. The auditor’s decision to qualify an opinion, or even disclaim an opinion because of a scope limitation, depends upon the auditor’s ability to form an opinion of the financial statements as a whole.

Auditors must also consider whether management’s refusal to furnish a written representation affects the reliability of other management representations received during the audit. This limitation may be sufficient to preclude an unqualified opinion and is ordinarily sufficient to cause an auditor to disclaim an opinion or withdraw from the engagement. Repeated, intentional misrepresentations could cause an auditor to resign from an engagement because she could not reliably assess whether the financial statements were materially misstated.

It is worth noting that the auditor’s Management Representation Letter is part of the auditor’s workpapers and would be seen by a third party only after the issuance of an enforceable subpoena or an inquiry made by a recognized investigative or disciplinary body, and would not be not available for public view.

Prior to signing the letter, management must completely understand each representation in the letter. Violations of this requirement are covered under Rule 13b2-2 of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, which states that no directors or officers of a company shall, directly or indirectly, mislead an accountant in connection with an audit or examination of the financial statements. Section 303(a) of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, Improper Influence on Conduct of Audits, Rules to Prohibit, repeats the same demand:

It shall be unlawful, in contravention of such rules or regulations as the Commission shall prescribe as necessary and appropriate in the public interest or for the protection of investors, for any officer or director of an issuer, or any other person acting under the direction thereof, to take any action to fraudulently influence, coerce, manipulate, or mislead any independent public or certified accountant engaged in the performance of an audit of the financial statements of that issuer for the purpose of rendering such financial statements materially misleading.

Not only does the Sarbanes-Oxley Act put emphasis on management’s representations, it also provides for larger fines and longer prison terms for executives prosecuted under the new law.

Management’s Responsibility for Financial Statements Letter. The Management’s Responsibility Letter is typically found just before or after the auditor’s opinion. The actual wording varies but generally indicates that management is responsible for the integrity and presentation of the financial data and statements in accordance with GAAP and for the maintenance of a system of internal controls. These voluntary responsibility reports are not required by the SEC requirement and not found in 10-K reports, although they are found in some annual reports (see Exhibit 3).

The authors reviewed a dozen annual reports and noticed that when this letter appears its title might be “Management’s Report” (McDonald’s), “Report of Management” (Textron), “Management’s Responsibility for the Consolidated Statements” (PG&E), or “Management’s Responsibility for Financial Reporting” (Enron; Lowe’s Companies). Of these five examples, the CEO and CFO signatures were found only on the Lowe’s and Textron responsibility reports. Given that signatures are not specifically required, for the other companies’ reports to show no evidence of signatures is not surprising and may be because executive management did not wish to sign off on statements for which they, prior to the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, were not required to be personally responsible.

In April 1979, the SEC proposed rules that would have required certain disclosures about a registrant’s internal accounting controls in annual reports and other filings. In June 1980, the SEC decided (Accounting Series Release 278) to withdraw the rule proposals based on, in part, its determination that private sector initiatives for public reporting on internal control had been significant and should continue. The SEC believed that this action would encourage voluntary initiatives and permit public companies a maximum of flexibility in experimenting with various approaches to public reporting on internal accounting control.

Such voluntary initiatives have now been superseded by section 302(a)(4)(D) of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, which states that “the signing officers have presented in the report their conclusions about the effectiveness of their internal controls.” The Office of the Chief Accountant told the authors that the SEC is currently discussing how and where this responsibility statement for internal controls will be implemented and believes that putting a responsibility letter in a company’s annual report will now become mandatory and that this same letter will be required in a company’s 10-K.

The Sarbanes-Oxley Act’s mandatory responsibility requirement would appear to be a clear improvement over previous practice. With potentially larger fines and even prison terms for noncompliance with Sarbanes-Oxley requirements, executive management will likely give more thought and care to the certification process.

Corporate Responsibility

Sarbanes-Oxley Act, section 302, “Corporate Responsibility for Financial Reports,” states that the CEO and CFO of each issuer shall prepare a statement to accompany the audit report to certify that “based on such officer’s knowledge, the financial statements, and other financial information included in the report, fairly present in all material respects the financial condition and results of operations of the issuer as of, and for, the periods presented in the report.”

The new requirement will be incorporated into the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. New Exchange Act Rules 13a-14 and 15d-14 will require an issuer’s principal executive and financial officers to each certify, with respect to the issuer’s quarterly and annual reports filed or submitted under section 13(a) or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, that the individual has reviewed the report, and based on her knowledge, the report does not contain any untrue statement of a material fact or omit to state a material fact that might make the statement misleading. It must also certify that, based on her knowledge, the financial statements and other financial information included in the report fairly present in all material respects the financial condition, results of operations, and cash flows of the issuer for the periods presented.

All U.S. companies with at least $1.2 billion in revenue in the past fiscal year were required to file their certification when filing their next periodic disclosure report due on or after August 14, 2002. Among the 971 such companies, 691 were required to submit certifications in August. Most companies complied; some companies, including Amazon.com, AMR Corp., Corning, and Federal Express, even submitted their certifications early. Approximately 16 companies filed explanations or other forms of certifications instead. Although companies such as Enron, WorldCom, and Adelphia were on this short list, other companies had legitimate reasons for missing the deadline. For example, if a CEO cannot be certain that the company’s financial statements are accurate and does not want to put herself in legal jeopardy by filing the SEC statement, she can file a sworn statement explaining why she cannot affirm the accuracy of the company’s financial reports.

Throughout

September 2002, the certifications began showing up on 10-K amendments, and

as companies with September year-ends came up, the certifications of CEOs

and CFOs began to appear on actual 10-K reports. The full title of the statement

is “Certification of Chief Executive (or Financial) Officer (sometimes

called the ‘Principal’ Executive or Financial Officer); Certification

Pursuant to 18 U.S.C. Section 1350, as adopted Pursuant to Section 906 of

the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002.”

Throughout

September 2002, the certifications began showing up on 10-K amendments, and

as companies with September year-ends came up, the certifications of CEOs

and CFOs began to appear on actual 10-K reports. The full title of the statement

is “Certification of Chief Executive (or Financial) Officer (sometimes

called the ‘Principal’ Executive or Financial Officer); Certification

Pursuant to 18 U.S.C. Section 1350, as adopted Pursuant to Section 906 of

the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002.”

Ongoing inspecting of certifications is no small task. Last year Alan A. Beller of the SEC’s Corporation Finance Division conceded that the agency could not monitor all certifications as it has for the largest companies. Of the roughly 68,000 annual quarterly and annual filings, the SEC staff will continue to review reports on a spot basis and rely on investors and the media for information about companies that fail to comply.

Reporting options. Companies have several options. They can sign the statements if they have confidence in them, or they can ask for a five-day extension for a Form 10-Q or a 15-day extension for a Form 10-K, which will also extend the due date for the related sworn statements. Another option is to submit an alternate document, not exactly in the form ordered by the commission, and hope that the SEC accepts it.

Other courses of action might meet with varied reactions from investors. For example, a company could restate past results and certify those results. But companies that substantially restate their earnings may run the risk of stockholder litigation, according to William S. Lerach, a partner of the law firm Milberg Weiss Bershad Hynes & Lerach. A restatement is an admission that the financial statements were materially false when originally issued, which gives any securities case an enormous boost. As Julia Angwin points out in “AOL Officials Take SEC Filing Down to the Wire” (Wall Street Journal, August 14, 2002), all the shareholder-plaintiff has to prove in today’s environment is that the improper accounting was done knowingly or recklessly. In some cases, however, companies may not be able to meet the reporting deadline for an understandable reason, such as a recent change in CEO or CFO, or a change of auditors.

Implications for CEOs and CFOs. The CEO and CFO could face significant penalties if they certify that the company’s books are accurate when they are not. The executives could face up to a five-year prison sentence, fines, and other disciplinary action such as civil and criminal litigation, as well as being barred by the SEC from ever serving as a corporate officer or director. Perhaps this “legal” responsibility, the basic premise that any wrongdoing will not go unpunished, will raise the stakes for those who would mislead investors and the public.

Consequently, now that executives are being held personally responsible for their companies’ financial statements, they must worry more than ever about their personal bottom lines. Indeed, a growing number of CEOs are researching legal ways to shield their money and property from shareholder lawsuits and federal prosecution. This is a complete reversal from how securities fraud cases used to be handled. Until the accounting scandals caused investors to distrust corporate America, a fraud case could be resolved by paying the fine out of the company’s coffers. In some cases, shareholder lawsuits accusing companies of fraud could be settled using money from an insurance policy. Executives rarely had to pay out of their own pockets.

The certifications will certainly require more due diligence for the CEO, the CFO, the audit committees, internal auditors, and the auditors in reviewing the financial statements and the underlying process in preparing the statements as well as at all other levels of financial management. And in the event of another failure like WorldCom or Enron, the certification by the CEO and CFO is unlikely to protect the auditors, the audit committee, and other senior accountants from legal liability. Until the first case is tried under the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, however, the full extent of this liability will remain unknown.

Putting Teeth into the Bite?

During his term as SEC Chairman, Harvey Pitt was quoted in the New York Times as saying, “[W]e are determined to give real teeth and meaning to the protections of the new law.” Conventional wisdom suggests that when people know they can and will be held accountable for their actions, their behaviors change. In these cases, therefore, the new rule should make it easier for government officials to make fraud cases against executives found to have intentionally filed false certifications under perjury charges. Roel C. Campos, a Texas businessman and former federal prosecutor before becoming an SEC Commissioner, described the new certification requirements simply. “What is being required,” he told the New York Times, “is that senior executive officials must say, ‘You have my word that what I am saying is accurate, and I realize if I fib, I will be in a heap of trouble.’”

According to some, however, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act has only limited benefits and it is uncertain how much these certifications will accomplish. In the current environment, companies already had sufficient incentive to ensure that their financials are accurate. For a company to knowingly publish false financial statements was already a crime; a new statute was not needed for that. Will additional legislation be sufficient to cause behaviors to change? Or will Congress’ attempt to demonstrate its engagement create unforeseen costs and liabilities without substantially influencing the illegal behavior at which it is aimed?

Added Value of the Certification

Given that executive management has already been asked to sign off on the Management Representation Letter and has had the opportunity to present a Management Responsibility Letter in the annual report, why would Congress pass an act requiring CEOs and CFOs to sign off on a separate certification statement? What value does the certification statement requirement add?

One explanation is that Congress’ overall intent was symbolic, to get the attention of executive management and give investors a greater sense of comfort following the Enron collapse. An alternative explanation is that Harvey Pitt found himself under attack and wanted to demonstrate that he could restore faith in the markets.

Symbolic acts can sometimes help, but substantive actions are what the economy really needs. The SEC should worry less about public relations and more about enforcement. Enforcement actions against those who perpetrated fraud in these cases will go a long way toward restoring investor confidence. Unless managers see other managers whisked away in handcuffs (e.g., Enron, Adelphia, and WorldCom) and facing prison time, they are unlikely to adjust their behavior. Enforcement of the laws is what is important, not the public relations value of a few more signatures on a certificate of integrity. Indeed, enforcement of these laws is what will bring out the added value of this statement and the other requirements of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act.

©2006 The CPA Journal. Legal Notices

Visit the new cpajournal.com.